Critical Thinking - Holman's hat: Communication Instructor

Main menu:

- My Instructor Hat

- My Researcher Hat

- My Personal face

- My Writing Pages

- My Teaching Pages

- ProjectPeople.Today

- Lovemore.Today

My Writing Pages

My Writing Page

A Thematic Sampling

The University of Arizona

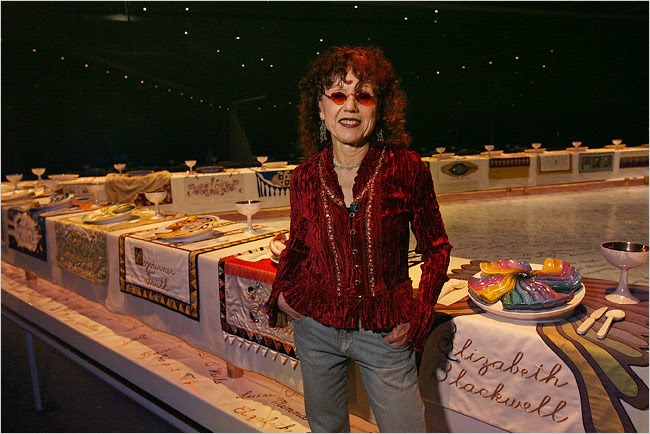

I first ran across passing mention of Judy Chicago’s art installation, The Dinner Party, in Foss’s (2009) chapter on ideological criticism. The author refers to an essay of her own that makes the claim that the Dinner Party “empowers and legitimizes women’s authentic voice through three primary strategies: ‘(1) The work is independent from male-created reality; (2) it creates new standards for evaluation of its own rhetoric; and (3) women are clearly labeled as agents,’” (Foss, 1988). Intrigued, I googled the installation.

I was swept away into a cavernous, darkened room, dramatically illuminating a large, banquet table in the shape of an open, equilateral triangle, 48 feet along each side. Along each arm of the table, 13 place settings (39 in total) sit on gracefully embroidered runners draped over an elegant, white table cloth. Each place setting consists of a goblet, napkin, porcelain flatware and a plate, meant to represent and commemorate influential, female change-makers from Western history. The settings are placed chronologically around the triangular table, which is itself placed on a raised dais of triangular, opalescent tiles. This arrangement is referred to as the Heritage Floor, upon which are transcribed the names of 999 other important female figures. Visitors are provided a path to walk around the installation, but kept apart from it by iron guide rails (Brooklyn Museum, n.d.). Six panels are hung in the entry hallway. Each is inscribed with one stanza of a short poem, “intended to convey Chicago's vision for a equalized world, one in which women's history and perspectives are fully recognized and integrated into all aspects of human civilization” (Brooklyn Museum 2, n.d.).

My first impression was wholly positive. I found myself wishing I could catch the red-eye to Brooklyn and see the Dinner Party in person. It was such an unusual piece; I felt there was ample room for further critical analysis of the ideological underpinnings of the various installation elements.

Lolette Kuby (1981) spoke of the publicity and PR that preceded the public unveiling of the Dinner Party. Like me, biased by Foss’s summary of its virtues and relevance, Kuby found herself swayed by the word-of-mouth hype sweeping through feminist circles: “I went to Judy Chicago's Dinner Party prepared to love it” (p. 128). Like her, the more I looked at the images – the hangings, the banquet table, the plates, the runners, even the way the installation is lit – the more an unexpected sense of disquiet began to grow. I was expecting to see an unbridled celebration of feminine accomplishment, coupled with an earnest expression of equality and an invitation to create a unity that transcended gender.

Instead, I saw a collection of heavy-handed symbols disturbed by internal conflicts. In my eyes, the instillation suffers from dialectical tensions that evoke subtle, underlying messages that undermine the higher purposes Chicago strived for, diffusing the power and punctum of the installation’s social commentary. While I admire what the artist set out to accomplish, to claim the rightful place of feminine accomplishment in Western history, I found myself seeing the deep reflection of hegemonic and normative influences that distort the intended surface meanings and weaken the artist’s proclaimed symbolism by propagating at unconscious levels the exact messages that she wishes to rewrite with expansive, empowering feminist meanings.

The purpose of this paper isn’t to make a particular artist wrong; but rather to ask ourselves “How does this exhibit undermine its central message of unity and equal recognition with contradictory symbolism?” The first step to creating a true “fourth wave” of feminism (see Rampton, 2014) is realizing that symbolic meanings are socially constructed (Craig, 1999). Protest can only move society so far, by raising awareness of unjust and unequal practices; after that, progress can come only by changing the underlying symbolic meanings that support unjust or unequal practices in the first place. For instance, it is the answer to the question “What does it mean to be a woman?” that cries out for a more modern and evolved set of symbolic, world-wide meanings. The more we can engrain a higher, more empowering set of meanings to our understanding of gender, the more societal behavior naturally, spontaneously changes to reflect that more evolved meaning. Focusing on issues – like unequal pay, or how pregnancy (or even the mere biological possibility of pregnancy) impact a career path (Carli, 2004) – can only ever be the first step; true change comes from reworking the deep, societal meanings that support inequality in the first place.

It is with these notions in mind that I will examine the Dinner Party, from a primarily ideological point-of-view. After all, our ideology is simply the set of meaning-making values, beliefs and filters through which we see the world. Our ideology is the broad umbrella, or framework, that holds our overall catalogue of what things mean. In the interest of space, I will not attempt to cover Chicago’s surface symbolisms, the meanings that the artist assigned to her artistic choices; but rather, I’ll examine specific elements within the installation to uncover the more subconscious meaning entanglements that undermine the surface symbolisms the artist hoped to evoke, weakening the intended message of the exhibit.

Ideological criticism takes the outer elements of an artifact, in this case all the pieces that make up the installation, and looks at them one-by-one. What are the meanings each element suggests? From those meanings, patterns of ideology can be identified. From those patterns, deeper meanings emerge (Foss, 2009).

For example, the first thing a viewer sees is a triangle, said to be an ancient symbol of the feminine; and because it is an equilateral triangle and the sides are the same size, unity (Brooklyn Museum, n.d.). However, when seen another way, the sides of a triangle only come together at each end. This single point of contact falls many points short of the unifying wholeness it was meant to represent. Likewise, the two points where the arms of the triangle do meet are empty of plate or goblet, offering no interaction or exchange from one arm to the other. Each point of intersection forms a sharp angle, like the head of a spear, keeping the triangle from folding into the perfect unity of a line or opening into the full harmony of a circle.

Moreover, a triangle has a solid base; but by the same token, it takes incredible energy to shift a triangle off that base, which privileges whatever side is “down.” A triangle represents stability (Bang, 2000) and stability is the playground of the status quo. Even though the sides seem to be the same, they are not, as the base of a triangle calls to mind a variation on the popular saying regarding communism: “Every side may be equal; but some sides are more equal than others.” The appearance of equality without its true meaning is nothing more than a sop intending to pacify the superficial. It is not a meaningful step forward.

From the triangles formed by the banquet tables, the floor, and by the lighting, the eye is naturally drawn to the place settings: the plates and the runners they sit on. The viewer is then confronted by 37out of the 39 plates, which are all variations of vulvar forms and butterfly shapes (Brooklyn Museum, n.d.). Without belaboring the point, if the exhibit were billed as erotic art, or as a celebration of the female form, then all would be well; but when it purports to represent and commemorate the historical contributions of woman by reducing those luminaries to a series of abstracted vaginas, then we must ask ourselves what message is really being sent. Because the Dinner Party is meant to carry a specific message, the vaginal iconography losses the charm and beauty of Georgia O’Keeffe and gains more the shock and outrage of Jean Kilbourne (2012), who in Killing Us Softly 4, said: “Woman’s bodies are dismembered in ads, hacked apart, just one part of the body is focused upon; which, of course, is the most dehumanizing thing you could do to someone.”

Further, even if we skip the arguments about why it’s not okay to objectify a woman’s genitals in advertising, but somehow it becomes okay as long as you consider yourself a feminist artist, we still have to consider the plates themselves. The table is set, awaiting the banquet such exquisite settings imply; but the food never arrives, nor are the guests invited to sit, for there are no chairs and the table is fenced off and inaccessible: 39 women invited to the table, but never actually dining there. The feast never materializes and the celebration never comes.

This brings us to the heritage floor and the 999 names that are inscribed on it without any discernable pattern, seemingly random and chaotic, as if the women to be remembered on the floor have no order or place of their own. Plus, it’s the floor. Floors are meant to be walked on, and is that the message we are supposed to take away from the exhibit? If asked, a guide will explain that the names on the floor are clustered around the place setting that matches their time period, but a viewer would never know this by just looking. Also, each name is rendered in the same handwriting, which further robs nearly a thousand women of individuality, swallowing them up, reducing them to a collective idea. The glare of the lighting washes out some of the names, rendering them illegible and leaving them in the “dark.” The table, with its cloth and runner, covers over all the names beneath it, leaving them in the obscurity the installation is supposed to rescue them from.

This brings us to the heritage floor and the 999 names that are inscribed on it without any discernable pattern, seemingly random and chaotic, as if the women to be remembered on the floor have no order or place of their own. Plus, it’s the floor. Floors are meant to be walked on, and is that the message we are supposed to take away from the exhibit? If asked, a guide will explain that the names on the floor are clustered around the place setting that matches their time period, but a viewer would never know this by just looking. Also, each name is rendered in the same handwriting, which further robs nearly a thousand women of individuality, swallowing them up, reducing them to a collective idea. The glare of the lighting washes out some of the names, rendering them illegible and leaving them in the “dark.” The table, with its cloth and runner, covers over all the names beneath it, leaving them in the obscurity the installation is supposed to rescue them from.From the above abbreviated examples, about which much more could be written, we can see that even common shapes like the triangle can come with entangling entailments that might undermine the discursive message of an artifact. We see this in empty plates and missing chairs, in names that cannot be seen, in vaginal imagery that fails to represent the wholeness that is a woman, or the breadth of her accomplishments, or to give her the acknowledgement and place in history that she deserves.

Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party is a significant, even monumental piece of art (Smith, 2002; Caldwell, 1981). Even if the ideological messages of the artist’s intent and some of the symbolic elements presented in the artifact conflict, even if surface and subconscious meanings clash – rather than view this as a negative observation, attacking the integrity of the artist, we can see it as an opportunity on two levels. First, we can appreciate the intent of the artist and all the ways she hit her mark (Barber; 1988, Lippard, 1980); while secondly, we can dig into deeper symbolic meanings that point to areas in what we think things mean that are in need of review or replacement. We can rethink the meanings of the symbols that surround us.

If the 3rd wave of feminism has been concerned with creating equal outcomes (Gruenwald, 2012); perhaps the 4th wave should be equally determined to co-create a more humanistic, empowering, and unbiased lexicon of meanings. We need new answers to old questions like “What does it mean to be a woman,” or “What does it mean to be a man.” By redefining these fundamental, societally created and reinforced norms, we change society. Rather than continuing to support dominant, oppressive hierarchies (of any kind), we can have unilateral opportunities; we can create a global celebration of diversity, a celebration of differences, without elevating some “differences” over others. That is feminism worth embracing. Like the runners in the Dinner Party, that is feminism worth embroidering upon the fabric of our consciousness.

References

Bang, M. (2000). Picture this: How pictures work. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

Barber, F. (1988). The critic's prodigal daughter: Feminist writings and art practice. Circa, 40, 32-35.

Brooklyn Museum (n.d.). Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art: The dinner party: Place settings. Retrieved from: http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/dinner_party/place_settings/

Brooklyn Museum 2 (n.d.). Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art: The dinner party: Entry banners. Retrieved from: http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/dinner_party/entry_banners/

Caldwell, S.H. (1981, January 1). Experiencing "The Dinner Party." Woman's Art Journal. 1(2), 35-37.

Carli, L.L. (2004). Gender effects on social influence. In Seiter, J.S. & Gass, R.H. (eds.) Perspectives on persuasion, social influence, and compliance gaining (pp. 133-148). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Craig, R. T. (1999). Communication theory as a field. Communication Theory, 9(2), 119-161.

Foss, S.K. (1988). Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party: Empowering of women’s voice in visual art. In B. Bane & A. Taylor (eds.), Women Communicating: Studies of women’s talk, (p. 17). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Foss, S.K. (2009). Rhetorical criticism: Exploration and practice (4th ed., pp.209-224). Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

Gruenwald, C. (2012). Misfit politics: Modern feminism means equal… outcome? Retrieved from: http://misfitpolitics.co/2012/03/modern-feminism-means-equal-outcome/

Kilbourne, J. (2012, August 24). Killing Us Softly 4 – Trailer [featuring Jean Kilbourne]. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jWKXit_3rpQ&feature=youtu.be

Kuby, L. (1981). The hookwinking of the woman’s movement: Judy Chicago’s the Dinner Party. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, 6(3), 127-129.

Lippard, L.R. (1980). Judy Chicago’s dinner party. Art in America, 4, 114-126.

Ramption, M. (2014, October 23). The three waves of feminism. Retrieved from: http://www.pacificu.edu/about-us/news-events/three-waves-feminism

Smith, R. (2002, September 20). Art review: For a paean to heroic women, a place at history's table. The New York Times. Retreived from: http://www.nytimes.com/2002/09/20/arts/art-review-for-a-paean-to-heroic-women-a-place-at-history-s-table.html