Theoretical Thinking - Holman's hat: Communication Instructor

Main menu:

- My Instructor Hat

- My Researcher Hat

- My Personal face

- My Writing Pages

- My Teaching Pages

- ProjectPeople.Today

- Lovemore.Today

My Writing Pages

My Writing Page

A Thematic Sampling

The Reel Model of Media Effects (RMME):

Examining the relationship between media message production

and audience consumption of mediated objects

Holman Meyerhoffer

University of Arizona

The Reel Model of Media Effects (RMME)

Technology is changing the way people live. Modern life is messy and hard and people often instinctively blame media. The history of media studies is rife with nearly axiomatic assumptions of how deeply television, movies, print, or the internet effect individual and society. Recent events, such as mass shootings or presidential tweeting continue to galvanize the study of mass media effects. Yet, there persist inconsistencies in the way media effects are conceptualized, operationalized, and discussed. Scholars lament that media effects overlap and that the constructs we use to analyze these effects have been only loosely defined, making cross comparisons of the findings difficult (e.g., Entman, 1993). I contend that at least in part this schism can be attributed to punctuation problems caused by looking at media effect constructs in isolation (e.g., twenty-five years later, scholars still cannot agree about the nature of the relationship between framing and agenda-setting).

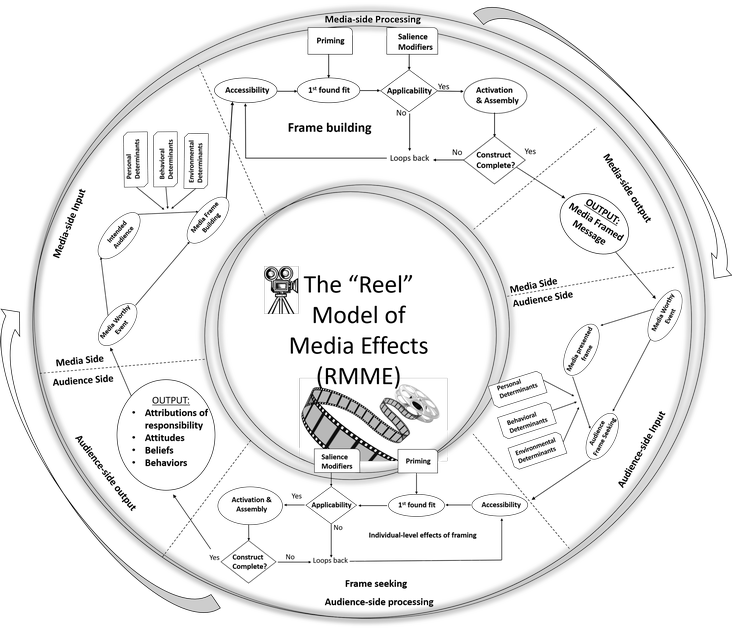

Thus, Scheufele (1999) proposed a cognitive process model featuring framing as the central organizing concept in political communication. This paper extends on Scheufele’s model by applying it more generally to iterative cycles of producing and processing media messages. Likewise, as the Scheufele model referred to the cognitive processes of both media producers and their audiences but did not specify what these processes are or how they function, this paper attempts to fill in the gaps.

Building from The Brain Up

It seems axiomatic that any deep discussion of how communication processes operate must abductively ground in the cognitive functions of the human brain and include observations from the neurology outward and from social behavior inwards to capture a complete picture. The human brain operates on symbols (Goffman, 1959), created by interpreting surges of chemical energy delivered interoceptively to the brain (Barrett, 2016). These interoceptive messages deliver information about everything going on internally to our bodies and externally to our environments. Our survival from moment to moment depends on how well and how quickly our brains can assemble this chemical energy into patterns and assess those patterns for meanings such as danger, food, shelter, safety, and sex. At the micro level, cognitive processes start by translating energy pulses into meaningful data and acting on that data (Barrett, 2016).

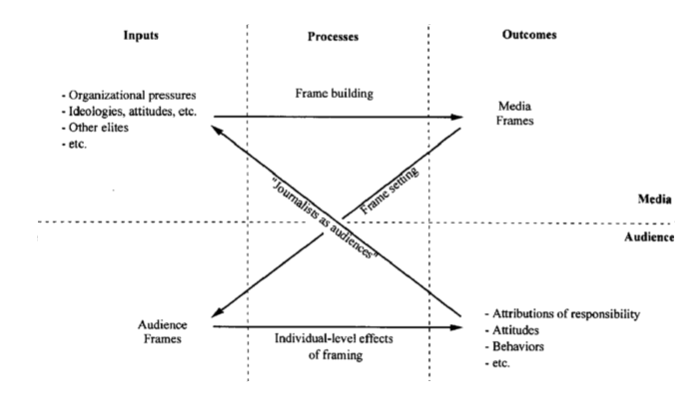

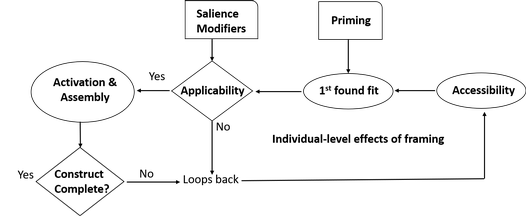

Scheufele’s (1999) process-based model (fig. 1)

In the interest of space, I’ll assume a basic understanding of Scheufele’s (1999) process-based model (see Figure 1) as an iterative cycle with six sections, three to describe the construction of media messages and three to explain audience interactions with media messages. In both cases, we can trace the flow of neurological inputs being cognitively acted on to produce a particular type of message on the media side or to interpret the message on the audience side. This flow occurs in three stages: input pre-processing, active construction, and post-processing. The output of media-side post-processing becomes an input source for audience interaction with a media message. The output of audience-side post-processing then feeds back on itself to influence media side message production, forming a punctuated yet unending utterance chain (see Baxter & Montgomery, 1996) between media and society as we see in Figure 1. This paper expands and clarifies this basic reciprocal flow of producer influencing audiences and audiences influencing producers in return, which we can now examine in more detail.

The Big Six

With Scheufele’s (1999) organizing structure in place, we can turn our attention to filling in each of the six functional elements of the Reel Model of Media Effects.

Media-Side Input: A Pre-Processing, Pre-Cognitive Stage

Mass media gives people a lot of ways to talk. Something occurs, something worth talking about and a big-bang of mediated messages follow. As a convenient place to begin, we can follow the lifecycle of a newsworthy event as it travels from initial insight to eventual mediated message appearing in public channels. Eventual testing of the model can assume this as a starting point in the cycle of media effects by controlling for preexisting input modifiers such as current public opinion, public interests, and media trends which are influences accounted for in our discussion of the media-side input stage.

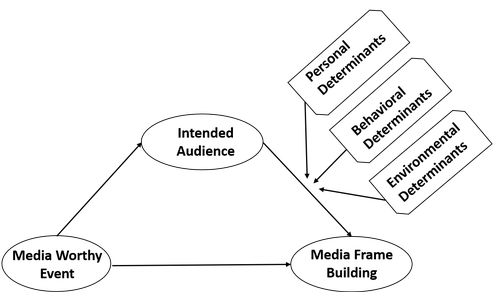

Media-side Input – First Pass (fig. 3):

A media message begins in the mind of the producer, yet a producer’s mind isn’t empty when the intention to create a media message first forms. The production of that message is subjected to a complex set of interwoven, moderating influences that both logically and phenomenologically exert liminal and subliminal pressures that shape both message content and the framing of that content.

A convenient way to represent this complex set of interacting, inter-influencing pressures is to configure them as a mediated/moderated model (see figure. 3).  The relationship between a media-worthy event and media frame building is explained by intended audience and moderated by a collective set of internal and external pressures. A producer creates a message with a specific audience in mind, the presumed values, norms, and demographics of that audience are a first level determinant of message frame and message content that is further modified by socio-cultural, environmental, and personal factors (Bandura, 1986) which we will examine below.

The relationship between a media-worthy event and media frame building is explained by intended audience and moderated by a collective set of internal and external pressures. A producer creates a message with a specific audience in mind, the presumed values, norms, and demographics of that audience are a first level determinant of message frame and message content that is further modified by socio-cultural, environmental, and personal factors (Bandura, 1986) which we will examine below.

The relationship between a media-worthy event and media frame building is explained by intended audience and moderated by a collective set of internal and external pressures. A producer creates a message with a specific audience in mind, the presumed values, norms, and demographics of that audience are a first level determinant of message frame and message content that is further modified by socio-cultural, environmental, and personal factors (Bandura, 1986) which we will examine below.

The relationship between a media-worthy event and media frame building is explained by intended audience and moderated by a collective set of internal and external pressures. A producer creates a message with a specific audience in mind, the presumed values, norms, and demographics of that audience are a first level determinant of message frame and message content that is further modified by socio-cultural, environmental, and personal factors (Bandura, 1986) which we will examine below.Media-side Input – adding another layer: Input Modifiers

Just as life is messy and complex, so too is the pre-processing stage. Yet, physicists can describe the entire physical universe in terms of the interaction of forces (Zukav, 1979). Human cognitive behavior is situated in the physical universe and can, therefore, be described using the same terms. Like gravity, there are constant neurological forces at play that influence the way media message are formed. Remember, the media-side input stage is pre-cognitive. The only cognitive event that occurs at this stage is the initial impulse or insight leading to an intent to create a message for a specific audience. Rather, this stage is a convenient place to consider the fundamental, ongoing influencers, drives, or pressures that shape human experience and by extension likewise shape media message construction.

Bear in mind that according to evolutionary theories, at the most micro-level, the function of the human brain is to preserve and pass on life (Schmid & Wuketits, 1987). Thus, its primary function is to make sense of its internal and external environments (Barrett, 2016). Sense-making assigns meanings to incoming neurological stimulation. Human beings operate based on the socially-created meanings assigned to these reoccurring, neurological patterns.

Borrowing from Bandura’s (1986) triadic reciprocal causation model, these reoccurring, neurological patterns form collective input modifiers that can be grouped categorically into three types (personal, behavioral, and environmental determinates). In this context, determinants refer to influences or drives that shape the way a person assigns meanings to things. According to Bandura, personal determinants are values, beliefs, attitudes, or qualities (such as self-efficacy, self-determination, or need for orientation) that color the meanings people assign to things (e.g., is it appropriate to portray nudity in public media?). Behavioral determinants are the socio-culturally driven meanings that drive personal actions or responses (e.g., how will nudity be handled in creating visual media?). Environmental determinates are assumptions of meaning placed on the actions and responses of other people, as well as the contextual/cultural/social factors that are also at play between an individual and her surroundings (e.g., why is there nudity in this message?).

Then these collective influences are themselves modified on the front end by a media producer’s intended audience and by that audience’s presumed response to the eventual mediated message, and on the back end by post hoc audience feedback (the viewer’s actual response). Intended audience and presumed response describe two forms of influence shaping a producer’s creative process while producing a media event. The creative process can be defined as frame building when the producer’s work is influenced by subliminal pressures that subconsciously shape the way a message is formed. The producer’s story must appeal to the needs and desires of an explicit audience and fulfill a specific purpose (some combination of the desire to inform, persuade, entertain, or generate profit).

Contrastingly, the creative process can be defined as frame manipulation when the producer knowingly, deliberately favors some element over another to create a specific, deliberate framing of a media event that purposefully privileges one potential interpretation over a competing alternative. Frame building and frame manipulation likely lie on a continuum such that media objects are produced through some combination of conscious intent to frame a piece in a particular way (e.g., a positivity bias or a conservative slant) and subconscious pressures that shape the way content is presented, or what content is excluded.

Further, the creative process is itself influenced by the producer’s experience with, and awareness of, how audiences have responded to previous media messages of similar type and content, in additional to post hoc audience feedback to the current message influencing follow up media projects. In the model, this is represented by audience-side outputs becoming media-side inputs that shape subsequent media message construction.

In summary, the media-input side of the Reel model is a pre-processing, pre-cognitive stage that sets boundary conditions or moderating influences that determine how subsequent information is sorted and filtered. This stage can be characterized as a complex combination of aggregated pressures.

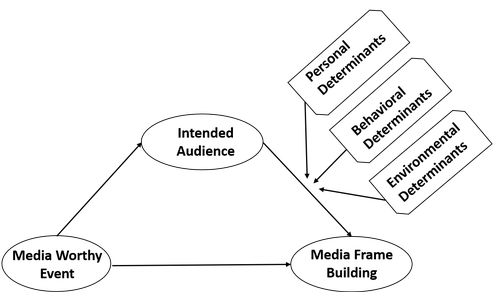

Media-side Processing: Gazing into the black box (fig. 4):

Two primary conditions govern the cognitive work occurring during the media-side processing stage: accessibility and applicability (see figure 4). A message is cognitively constructed from Lego-like building blocks (see Greene, 1984) of associated neurological patterns that form what I will call primary conceptual nodes (PCN’s) that are linked by association or similarity. This is in alignment with associative network theories positing multivalent, non-hierarchical neural structures (e.g., Anderson, 1983; Lau, 1986, 1989). Whereas a “node” can refer to “any particular element … in a network” (Price & Tewksbury, 1997, p. 186), a primary conceptual node is limited in scope to the smallest conceptual units that can combine to form meaning, a necessary level of distinction when considering, for example, the cognitive processes of priming.

Just as language is built up from phonemes that form syllables that join together into words, and just as words are arranged for meaning to make a sentence and sentences group together in paragraphs, primary conceptual nodes combine and recombine continually in what Anderson (1983) referred to as tangled hierarchies. Primary conceptual nodes are linked to construct concepts and concepts are arranged to form meaningful descriptions of events across time (Barrett, 2016).

During the processing stage, each potential PCN able to slip through the filtering effect of the input modifiers is then accepted or rejected based on accessibility and applicability, and if accepted the PCN is passed downstream to a metaphorical landing stage where neurological stevedores gather each PCN and stack them up in meaningful piles (associated synaptic connections). We can employ the visual metaphor of a 3D printer building up a construct layer by layer through recurrent passes through the processing stage until a media object is complete in both content and the way that content is framed. This mental representation is then transformed into its corresponding media element (e.g., this could include anything from a word on the page to a complete news article, a frame on film to a complete documentary, and so forth).

The input stage metaphorically provides a shaped template that all potential PCN’s drop into as the processing stage tests them for accessibility and applicability, and either passes them downstream for assembly or repeats the process to retrieve a more contextually relevant PCN and then retest for goodness of fit and so on.

Media-side Processing – Adding another layer:

Accessibility

Accessibility refers to how readily a piece of information in the human brain can be retrieved and called up for further examination or processing compared to any other potentially relevant data. Accessibility operates like reaching into a silverware drawer for a soup spoon: in the absence of a more compelling reason to reach deeper in the drawer, we will grab the first spoon that comes to hand. So too with accessibility. To continue our metaphor, from among all the different types of forks, knives, spoons, or utensils the brain could potentially find in its working storehouse of knowledge and pull up for potential processing in working memory, the human mind filters, sorts, grabs the first soup spoon it can find, and tosses it down the processing chain.

The soup spoon represents the first primary conceptual node found that contextually fits, links with, or associates with the input stimulus (the media-worthy event) that wasn’t excluded from potential consideration by the input modifiers. If the spoon is applicable, then it is passed on. If the spoon doesn’t fit, it is tossed aside, and the next spoon found is then tested in turn.

Accessibilityà1st found fitàApplicability

Cognitive miserliness causes the brain to process accessibility based on what I will call first found fit. Cognitive miserliness can be thought of as the balancing point between the problem-solving power of focused attention and the high metabolic expense such intensive cognition requires (Toplak, West, & Stanovich, 2014). The brain automates cognitive processing to increase metabolic efficiency. The producer’s brain, like water, always seeks the twin path of least resistance and greatest ease as it flows down its vast network of neurological connections. Less resistance and greater ease are functions of both recency, frequency, and intensity (Price & Tewksbury, 1997) or what Scheufele (1999) referred to as chronic or temporary factors underlying accessibility. Perhaps both recently activated and well-practiced neurological patterns have lower activation thresholds (see Greene, 1984), and are thus more likely to fire in response to contextual associations with the media-worthy event.

To take it one step deeper: in response to input side pressure, combined with cognitive miserliness, the producer’s brain seeks the first primary conceptual node (PCN) it can draw up from long-term memory stores based upon neurological connections between the current media-worthy event, pre-existing experience in memory (anything that bears sufficient resemblance to any of the salient elements of the media-worthy event), and the need to present the media-worthy event to an intended audience. In other words, the brain predicts the most appropriate link among all possible relevant matches based on the easiest link to find or activate (Barrett, 2016). Then “goodness of fit” determines applicability and the process repeats until enough primary conceptual nodes are tagged as relevant and passed on for inclusion and assembly in the emerging mental media construct.

Adding another layer: the modifiers

Priming moderates Accessibility

Priming has a direct effect on accessibility. Priming describes the process by which nodes become accessible. Concepts (in the form of primary conceptual nodes) interconnect in tangled hierarchies where each concept is cross-linkable along multiple neural sub-networks (Anderson, 1983) which in turn form cascading concept maps (Barrett, 2016), or explain the spread of knowledge activation patterns (Price and Tewksbury, 1997). Given the constraining necessities governing cognitive miserliness (Toplak, West, & Stanovich, 2014), it logically follows that priming determines the order potential PCN’s are examined for applicability.

Priming in this view can be thought of as an after-effect of previous iterations of the processing cycle that leaves a particular PCN (or pre-existing assemblage of PCN’s, see Greene, 1984) still buzzing and ready to go. If we return to the silverware drawer, then the mind’s sorting of soup spoons is based on priming effects. Priming gives one PCN top-of-mind salience compared to other potentially applicable concepts. Defined in this way, priming explains temporal accessibility and is the gatekeeper governing what concepts pass on to the applicability check that forms the back end of the processing stage.

Applicability

Applicability refers to whether the PCN passed forward from first found fit continues to satisfy situational and relevance boundary conditions upon closer examination. Revisiting the silverware drawer analogy: accessibility, acting in concert with collective pre-processing pressures provides a soup spoon, but is it the right spoon for the job? Applicability is the next set of filters a potential PCN must pass. PCN’s judged applicable pass downstream and become part of the output package, a media framed message. This cycle of input processing happens until all the elements constituting the media-worthy event have been selected and processed (or rejected and filtered out), resulting in a completed, framed, media presentation of the event at hand that first forms as a mental representation that informs and shapes the physical production of the mediated message.

Adding another layer: the modifiers

Salience moderates Applicability

Space constraints allow only brief mention of various potential factors that influence how salience moderators effect PCN applicability checks. I will reference three: agenda-setting effects, moral intuition, and degree of group identity. Even this brief mention serves to illustrate how the model situates the various forces at play in a logical order that allows for extended theoretical development within the model without losing the big picture.

Agenda-setting

The Reel model suggests that a full discussion of agenda-setting must be situated in three categories, and, therefore, necessarily operates as separate cognitive constructs. First, we will consider agenda-setting as a micro-level, media-side process that moderates issue applicability. In that context, agenda-setting influences the salience that gets assigned to potential PCN’s as they are tested for inclusion and is thus a second order process that modifies frame selection (both frame-building and frame-manipulation), rather than the other way around as McCombs, Shaw, and Weaver (1977) suggested. Here, agenda-setting is the function of the current processing cycle and thus logically works within the context of framing building as a salience modifier acting on applicability.

Second, agenda-setting as a macro-level effect moderating the input and output stages, McCombs, Shaw, and Weaver’s (1977) classic sense of agenda-setting as describing media effects on public perception of social issue relevance. Here, agenda-setting is a temporal factor that results from previous processing cycles influencing the current processing cycle. Third, agenda-setting as a media subtype moderating frame manipulation: a media message specifically intended as an influence attempt, i.e., agenda-setting as a message type rather than as a cumulative or moderating message effect.

Moral intuition

Alongside agenda-setting effects, we can position Tamborini’s (2011) work on moral intuition as another moderating influence on applicability. As values affect both judgment and behavior (Torelli & Kaikati, 2009), it is reasonable to say that the values a producer or an audience member holds, alongside their sense of moral intuition, will moderate micro-level applicability checks during the processing stage. Haidt and Joseph (2008) outlined five categories, or modules, that underlie moral intuition, including authority, loyalty, purity, fairness, and harm/care. It makes sense that these same five categories would act as applicability moderators, and that module salience would be a function of the intersection between the media-worthy event and the related PCN weighed against Tamborini’s (2011) module relevant content, module exemplars, and module adhering content. These three factors all work in concert to form a current, contextual, module-based moral evaluation that then filters potential primary conceptual nodes for moral acceptability as a moderating applicability check.

Group membership, group identity & current group composition

I suspect that group membership, degree of group identity, and when not alone, current group composition (the people all around you) all influence salience in the context of the media-worthy event. Both producers and audience members are influenced by group norms and group power distribution within and across multiple levels of group membership. These are cognitive constructs maintained in the mind that are composed of the physical positioning of an individual among all other people in the physical environment and the mental positioning of that individual in terms of status and relationship compared to those others sharing the same public or private space. It seems reasonable that both the physical make-up of surrounding people and the mental representation of self in relation to those surrounding people will affect potential meaning-making activities (Goffman, 1959), such as judgments of applicability during the processing of a media message.

The more a person identifies with a group, relative to the media-worthy event, the more likely group norms will influence which moral intuition modules become most salient at a given moment. In turn, moral intuition salience will privilege some potential PCN’s over others that might have been chosen under the influence of a different physical group or might have been chosen if the media-worthy event more closely aligned with one group over another, and vice versa. Regardless, once a PCN overcomes the filtering effects of accessibility and applicability it gets tagged for assembly into concepts that form meaningful collections that group together to create a media message.

Assembly

The assembly process continues until a complete story is constructed, one PCN at a time. For example, a complete construct might consist of a single word during the beginning of the creative process or the final touch on a completed media project. Along the way, each needed element to fill in a whole media picture is sorted for accessibility and then applicability and then loops until the message completeness check equals yes. Each cycle of the loop either corrects itself by making a second prediction of the next easiest link to activate, or if the fit is good, tags the concept and moves it downstream. Each tagged PCN adds in another conceptual linkage until a complete construct is assembled. That construct (and all the individual PCN’s that are linked together to form that construct) in turn links into a larger assembly of meaningful, associated constructs. This continues until a whole media message is mentally framed, assembled, and translated into the physically produced media message that emerges as output.

Media-side Output:

Now that the media message has been assembled into a coherent product it passes from the processing stage to the output stage as a fully framed media message (Scheufele, 1999). The “reel” turns and the final media object flows into the public purview as audience-side inputs being cognitively processed by media consumers.

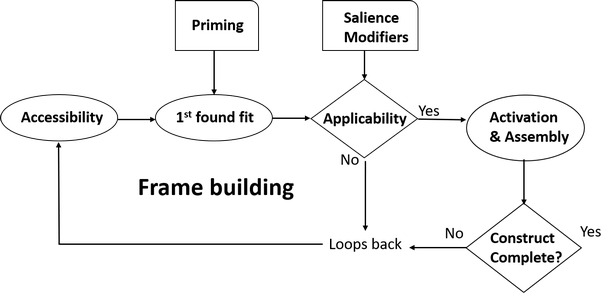

Audience-side Input (fig. 5)

One advantage conferred by the Reel framework is that audience-side processing activates the same essential neurological processes as described on the media-side. Consequently, we can limit the discussion to what differs as audience members process media messages, which I will define as frame seeking. The audience side of the Reel framework begins with the presented media frame being made available for consumption by individuals. As such, the presented frame represents one way an audience could potentially understand the message or issue at hand, but the media producer has no way to predict how any one individual will assemble their final audience frame (see figure 5). This allows for exacting examination of both selective exposure and individual effects.

Just as during the media-side input stage, the audience-input side of the model is a pre-processing, pre-cognitive stage that sets boundary conditions or moderating influences that shape what primary conceptual nodes are made accessible for inclusion compared to other potential PCN’s that are filtered out and never appear in working memory. This inclusion/exclusion process can be visualized as a series of yes/no decision trees acting both individually and as aggregated pressures that shape the final message outcome by privileging certain potential PCN’s over others.

How the object is framed or understood from the audience’s perspective depends upon a similar combination of personal, behavioral, and environmental determinants which parallel the media side and also include need for orientation as a frame seeking driver. Need for orientation refers to a person’s information seeking behaviors and describes "individual differences in the desire for orienting cues and information [and] explains differences in attention to the media agenda and, consequently, differences in the degree to which individuals accept the media agenda" (Chernov, Valenzuela, and McCombs, 2011, p. 143).

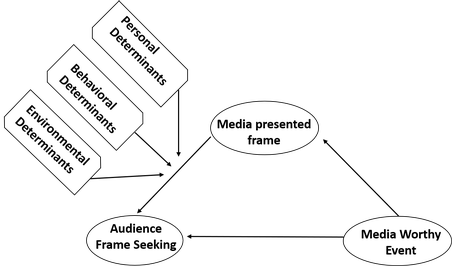

Audience-side Processing (fig. 6)

Audience-side processing mirrors media-side processing, including the complex interplay of priming modifying accessibility and salience modifying applicability, and results in an audience frame (see figure 6).

The audience frame may or may not align with the media frame and thus accounts for individual differences in media effects. We can define media-side processing as frame building or frame manipulation, and audience-side processing as frame seeking. Using this nomenclature allows very clear discussions of what stage of media message production or audience-side consumption is being examined.

Audience-side Output: post-processing and enactment stage

When a media message has been fully processed and understood through the resultant audience frame, according to Scheufele (1999) two interesting things emerge: first, the actual effect of the message on the individual herself which can result in an array of outcomes. The audience-side output results in an amalgamation of the following: attributions of responsibility, and some combination of reinforcement or changes in a person’s attitude, value, belief, and behavior. The second effect of audience-side processing occurs as media content begins to generate feedback and media producers respond. Indicators of audience response become inputs that reignite the media creation process. Audience side feedback becomes media side input.

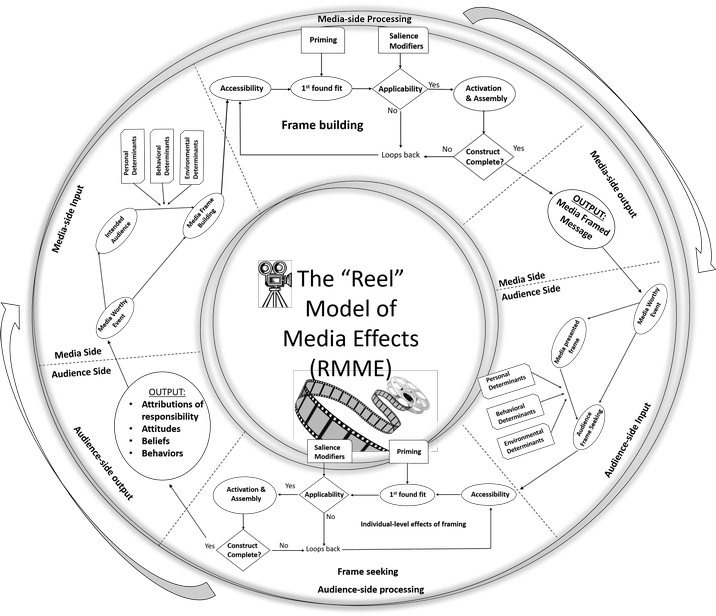

Big Picture: (Fig. 2) The Reel Model of Media Effects (RMME)

Having gone over the reel model in some detail, we can examine the completed framework as a visual metaphor (see figure 2) representing the big picture interplay of media effects between media producers and their audiences, as well as the dynamic, reiterative, cyclic nature of the micro-level neurological activity that keeps the metaphorical reel turning. It offers a visual reminder of all the model’s stages and how the output of each stage becomes the input of the following stage in an endless ouroboros of the brain (see figure 2).

The parsimonious nature of the individual stages within the model eases the complexity of considering the broader, interconnected relationship between media effect factors such as priming and agenda-setting which, when considered individually, obscure the logical, inter-related flow of influences that defy operational separation because they never occur in isolation.

Agenda-setting is a function of framing because all media messages are framed as they are created and framed a second time as they are consumed by an audience. Even “scientific objectivity” is simply a type of framing that includes one PCN and excludes another. Yet, the cumulative weight of media frames feeds back to influence the topical salience of later media messages, which potentially changes the way that subsequent message is framed by media and interpreted by the public. The circular, reciprocal, micro-level flow between framing, priming, and agenda-setting is mirrored by the macro-level relationship connecting media producer and media consumer.

Further research

This presentation of the reel model of media effects constitutes the briefest, introductory essay of the potential inherent in examining media effects through this organizing framework. The Reel model offers conceptually logical ways to deeply consider any individual part of the overall picture of media effects without losing sight of how these mutual influences work together. The conceptual nature of the current work can, therefore, be filled in by mapping extant theory into the appropriate section of the model, as well as through developing new theories of media effects.

For example, selective exposure research fits handily into the audience-input side of the reel and yet would also have a secondary effect on the media-input side. After all – as Scheufele (1999) pointed out, media producers are simultaneously media consumers and the media messages they produce cannot arise from concepts never encountered or media messages never selected. Likewise, individual effects research falls naturally into the audience-side processing stage. Yet by considering individual effects through the lens of the reel model, scholars can keep in mind the complexity that arises from individual enactments of collective symbolic representations, and so forth.

The final wrap up of the reel model is a simple reminder that life is messy and studying it matters. Technology is changing the way people live, and media effects are not going to become suddenly irrelevant. Rather, as the technological reach and complexity of humanity increases, so too does the importance of understanding how media messages influence both the individual and her society, and the reel model of media effects gives us a powerful framework to gain just that understanding.

References

Anderson, J. R. (1983). The architecture of cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall

Barrett, L. (2017;2016;). The theory of constructed emotion: An active inference account of interoception and categorization. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 12, 1-23. doi:10.1093/scan/nsw154

Baxter, L. A., & Montgomery, B. (1996). Relating: Dialogues and dialectics. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Chernov, G., Valenzuela, S., & McCombs, M. (2011). An experimental comparison of two perspectives on the concept of need for orientation in agenda-setting theory. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 88, 142-155. doi:10.1177/107769901108800108

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday.

Greene, J. O. (1984). Cognitive approach to human communication: An action assembly theory. Communication Monographs, 51, 289-306. doi:10.1080/03637758409390203

Lau, R. (1986). Political schemata, candidate evaluations, and voting behavior. In R. Lau & D- O. Sears (Eds.), Political cognition: The 19th annual Carnegie symposium on cognition (pp. 95—126). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Lau, R. ( 1989). Construct accessibility and electoral choice. Political Behavior, 11, 5-32.

McCombs, M. E., & Shaw, D. L. (1972). The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly, 36, 176-187. doi:10.1086/267990

Price, V., & Tewksbury, D. (1997) News values and public opinion a theoretical account of media priming and framing. In Barnett, G. A., & Boster, F. J. (Eds.). Progress in Communication Sciences, 173-212.

Scheufele, D. A. (1999). Framing as a theory of media effects. Journal of Communication, 49, 103-122. doi:10.1093/joc/49.1.103

Schmid, M., & Wuketits, F. M. (1987). Evolutionary theory in social science. Dordrecht: Springer, Netherlands.

Tamborini, R. (2011). Moral intuition and media entertainment. Journal of Media Psychology, 23, 39-45. doi:10.1027/1864-1105/a000031

Torelli, C. J., & Kaikati, A. M. (2009). Values as predictors of judgments and behaviors: The role of abstract and concrete mindsets. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96, 231-247. doi:10.1037/a0013836

Zukav, G. (1979). The dancing wu li masters: An overview of the new physics (1st ed.). New York, NY: Morrow.